Last month, a video was trending on social media showing a Canadian woman explaining that she had a 13-month wait for a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) test to check for a brain tumor.

On X, formerly known as Twitter, community notes popped up to say that the video was misleading. “Priority is decided by physicians, not the province,” wrote one commenter. Another noted that wait times did vary by province.

None of this, however, detracts from the core truths: Canadian health care is not free and it has two prices: the taxes Canadians pay for it and the wait times that make Canadians pay in the form of service rationing.

Canada’s publicly provided health care system actually requires rationing in order to contain costs. Because services are offered at no monetary price, demand exceeds the available supply of doctors, equipment, and facilities. If the different provinces (which operate most health care services) wanted to meet the full demand, each would have to raise taxes significantly to fund services. To keep expenditures down (managing the imbalance from public provision) and thus taxes as well, the system relies on rationing through wait times rather than prices.

The rationing keeps many patients away from care facilities or encourages them to avoid dealing with minor but nevertheless problematic ailments. These costs are not visible in taxes paid for health care, but they are true costs that matter to people.

All this may sound like an economist forcing everything into the “econ box,” but the point has also been acknowledged by key architects of public health care systems themselves. Claude Castonguay, who served as Quebec’s Minister of Health during the expansion of publicly provided care, conceded as much in his self-laudatory autobiography. The reality, he explains, is that eliminating rationing would imply significantly higher costs — costs that politicians are generally unwilling to justify through the necessary tax increases. Multiple government reports also take this as an inseparable feature of public provision — even though they do not say it as candidly as I am saying it here.

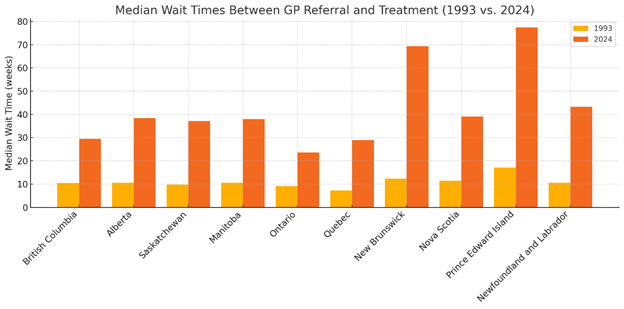

To illustrate the magnitude of rationing (and the trend), one can examine the evolution of the median number of weeks between referral by a general practitioner and receipt of treatment from 1993 to 2024. In most provinces (except one), the median wait time in 1993 was less than 12 weeks. Today, all provinces are close or exceed 30 weeks. In two provinces, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island, the median wait times exceed 69 weeks. For some procedures, such as neurosurgery, the wait time (for all provinces) exceeds 46 weeks.

Figure 1:

Estimating the full cost of health care rationing is far from straightforward. The central challenge lies in balancing data reliability with the breadth of conditions considered. While some procedures and ailments are well documented, they represent only a subset of those subject to rationing. For many other conditions, data quality is limited or inconsistent, making comprehensive analysis difficult. As a result, most empirical studies focus narrowly on areas where measurement is more robust, leaving much of the total cost unaccounted for.

In 2008, the Canadian Medical Association (CMA) released a study estimating the economic cost of wait times for four major procedures: total joint replacement, cataract surgery, coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), and MRI scans. For the year 2007, the CMA estimated that the cost of waiting amounted to $14.8 billion (CAD). Relative to the size of the Canadian economy at the time, this represented approximately 1.3 percent of GDP. That study did not include, as one former president of the CMA noted, $4.4 billion in foregone government revenues resulting from reduced economic activity. It also does not include the cost of waiting times for new medications.

These procedures do not capture the full scope of delays in the system and only a few procedures — and the analysis focused only on an arbitrary definition of “excessive” wait times. In 2013, the Conference Board of Canada found that adding an extra two additional ailments boosted the cost from $14.8 billion to $20.1 billion.

Another study used a similar method, but considered the cost in terms of lost wages and leisure. It arrived at a figure, for 2023,of $10.6 billion or $8,730 per patient waiting.

One study attempted to estimate the cost of rationing in terms of lives lost. This may seem callous, but lives lost means lost productivity — a way to approximate the cost of wait times. One study found that one extra week of delay in the period between meeting with a GP and a surgical procedure increased death rates for female patients by 3 per 100,000 population. Given that the loss of a life is estimated at $6.5 million (CAD), this is not a negligible social cost in terms of mortality.

And all of this for what? One could argue that these wait times come with good care once obtained. That is not true either.

Adjusting for the age of population, Canada ranks (out of 30):

#28 in doctors

#24 in care beds

#25 in MRI units

#26 in CT scanners

In one comparative study examining care outcomes — such as cancer treatment, patient safety, and procedural success — “Canada performed well on five indicators of clinical quality, but its results on the remaining six were rated as either average or poor.” This is despite, after again adjusting for population age structure, Canada ranking as the highest spender among a group of 30 comparable countries.The reality is that, whatever nuances one wishes to introduce — whether in good faith, pedantically, or simply to troll — the core message of the viral video remains accurate: Canadian health care works well for those who can afford to wait. To which I might add: wait very long.